Altar Q

Location: At the base of Structure 10L-16

Dates:

- 5 Kaban 15 Yaxk'in 8.19.10.10.17 / September 6, 426 CE

- 8 Ajaw 18 Yaxk'in 8.19.10.11.0 / September 9, 426 CE

- 5 Ben 11 Muwan 8.19.11.0.13 / February 9, 427 CE

- 6 Kaban 10 Mol 9.16.12.5.17 / June 28, 763 CE

- 6 Ajaw 13 K'ayab 9.17.5.0.0 / December 29, 775 CE

- 5 K'an 12(13) Uo 9.17.5.3.4 / March 2, 776 CE

King: 16 - 1

Measurements: 2.5 feet x 4 feet x 4 feet

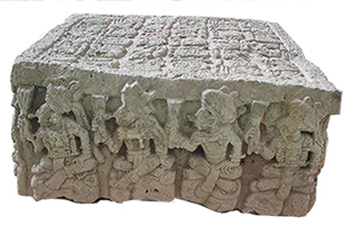

Altar Q in Front of Temple 16

Photograph Courtesy of Dr. Clark Erickson

Before Altar Q, Copan’s king lists included the censers in the Chorcha tomb, which were complete for the time but revealed little textual information, or the Hieroglyphic Stairway, which provided great textual information that required a great effort to reorder, translate, and contextualize. Altar Q is the most complete in that it includes all sixteen recognized kings in Yax K’uk’ Mo’s lineage.

The altar was carved out of volcanic tuff, mined from north of the Acropolis. Altar Q rests upon four cylindrical feet which also bore the names of kings, though their writing has since been worn away by the elements (Herring 2005, 210). On the top of the altar, thirty-six glyphs are carved, with the text comprised of three sets of two columns of glyphs. Sixteen figures in total are found on its sides, with four figures to a side, each sitting on a glyph. On three sides, each of the figures sits facing in one direction. Eight face left while four face right (Baudez 1994, 95). They sit in a circle, facing the two figures who meet in the west side of the altar. All but these two figures hold a fan-like object in their hand. In the center of the west side, the figure to the right hands the figure to the left a scepter-like object, and two glyphs are suspended between them. Notably, the figures on the sides appear as they would from the opposite side of the circle from where they are positioned (Herring 2005, 211). Thus, the figures, who face out toward the viewer, project the center of the circle out to the altar’s audience, drawing them into the action of the circle.

The text on the top of the monument says that on September 6, 426, Yax K’uk’ Mo’ as Ajaw K’uk’ Mo’ underwent ch’am-K’awiil, or took K’awiil at Wiin te’naah, or the Origin House (Stuart 2004, 233, 236-237). Through this ritual, Ajaw K’uk’ Mo’ became Yax K’uk’ Mo’ (Stuart 2004, 233). Three days later, he left the Origin House believed to be in Teotihuacan (Stuart 2004, 235, 237). One hundred fifty-three days later, the journey ended and the West Kaloomte’, or Lord of the West, arrived in Copan (Stuart 2004, 238). Seventeen k’atuns later under Yax Pasaj’s rule, either the altar itself or Temple 16 was dedicated, and sixty-four days later the rites were concluded. Sixty-four as the cube of four may have served a symbolic purpose adding to the altar’s reference to the four sided cosmos (Stuart 2004, 239). The altar itself is dedicated to the Founder as his memorial (Stuart 2004, 227). On the front of the Altar, in between Yax K’uk’ Mo’ and Yax Pasaj, is the sixeenth king’s accession date 6 Kaban 10 Mol, or June 28, 763 (Baudez 1994, 97; Martin and Grube 2008, 209). Surrounding this glyph, Yax K’uk’ Mo’ hands the k’awiil scepter to Yax Pasaj, justifying his rule (Martin and Grube 2008, 209).

From the top, left to right, Altar Q West, South, East, and North

Photos (Edited) Courtesy of Dr. Clark Erickson

Along the sides, Yax K’uk’ Mo’ and K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil do not sit on their name glyphs, unlike the other kings. Yax K’uk’ Mo’ sits on an Ajaw glyph with his name given in his headdress. One can find glyphs for K’inich and Yax in the front feather, a quetzal feather in the back for K’uk’, and a macaw eye for Mo’ (Sdouz 2015, 102). The twelfth ruler sits on the glyphs for “5 k’atuns”, referring to his being over eighty at his death (Sdouz 2015, 106). For Yax Pasaj, his name is split between his seat and his headdress, with Chan or sky and Yoaat found in his headdress (Sdouz 2015, 107, 109). Another interpretation is that he wears a headdress invoking Chaak - the rain god - asserting his status as a rain maker, or the fertile rain that falls from the rising smoke of the ancestors (Taube 2004, 295).

The rest of the kings sit on their name glyphs. Furthermore, all of the kings except for Yax K’uk’ Mo’, Waxaklajuun Ubaah K’awiil, and Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat wear turbans. Waxaklajuun Ubaah K’awiil also potentially wears his name - Eighteen Rabbit - in his headdress (Sdouz 2015, 109). The turbans are rare in the region and relatively rare at Copan, only appearing on seven stelae, two altars, and one bench. Notably, none of these monuments precede K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil (Sdouz 2015, 108).

Each of the kings except for Yax K’uk’ Mo’ wear one of five combinations of designs for their pectoral. Out of respect for the Founder, he only wears one tubular bead. Ruler 2, K’altuun Hix, and Ruler 6 all wore the serpent bar with the day glyph Ik surrounded by forked tongues above an assortment of beads below. Similarly, Ruler 3, Ruler 5, Ruler 10, Ruler 7, and Ruler 14 wear a Witz head surrounded by forked tongues with an assortment of beads hanging below. Ruler 8, Ruler 9, and Ruler 12 wear a tubular bead with three beads on each end and two sets of two beads hanging below. Ruler 13 and Ruler 15 wears a combination of the tubular bead with the bead sets and the Ik glyph assortment. Yax Pasaj sets himself apart by wearing both the tubular bead with bead sets with a plain tubular bead below (Sdouz 2015, 111).

When Altar Q was created in 775, Copan was roughly celebrating the new k’atun, the seventeenth since the change of the bak’tun which Yax K’uk’ Mo’ had overseen (Herring 2005, 217). Yet, Yax Pasaj did not have the resources or labor needed to create a large scale monument or temple. He remodeled existing sites and created several altars, which compared to stelae were small in stature (Martin 2008, 209). Altar Q was an addition to Structure 10L-16, a temple to Yax K’uk’ Mo’. The sixteenth king placed the altar at the bottom of the stairway to the temple and named it the Yax K’uk’ Mo’ Altar (Herring 2005, 218). Beneath the altar he buried fifteen jaguars, one for each of his predecessors (Fash 1991, 170). Jaguars were recognized as the way or the spirit guides of the kings, providing an impressive gift to his predecessors (Fash, Fash, and Davis-Salazar 2004, 70).

Yet, Altar Q and its offering had structural flaws that hint at Copan’s decline. While the sixteenth king impressively sacrificed fifteen jaguars to invoke his ancestors as protectors of the city, two of these jaguars had not yet reached adulthood (Fash 1991, 170). Copan did not have the resources to offer a perfect sacrifice. On the altar itself, text had been forced to fit on the space provided with dates spilling over into the next column, and one date in particular is impossible for the time period, indicating a carving mistake (Sdouz 2015, 83-85). The apparent flaws on this altar highlights the lack of care able to be afforded to monument production at this time.

In depicting the founding event as well as the entire king list up until the sixteenth king, the sixteenth king was able to celebrate the glory of Copan, recalling the bounty of its prime. Yax Pasaj chooses to have Yax K’uk’ Mo’ dressed in his Teotihuacan garb with his feathered shield and Tlaloc goggles, recalling the moment when he seized power in the great city. References to Teotihuacan rose in the Late Classic period, in particular after the crushing loss of Waxaklajuun Ubaah K’awiil (Fash 2004, 264).

Having asserted the glory of Copan’s founding and its history, Yax Pasaj inserts himself into the narrative and thus justifies his rule. The inscription at the top of the altar ends with Yax Pasaj creating the altar and later seizing the k’awiil himself, which is depicted on the west side of the altar. This west to east motion can even be seen as Yax K’uk’ Mo’ being resurrected through Yax Pasaj’s efforts if not through Yax Pasaj himself (Taube 2004, 295). In this altar that is created at the foot of the temple for the founder and is dedicated in his name, the focus of the narrative ultimately shifts to the accession of the sixteenth king. The glyph between Yax K’uk’ Mo’ and Yax Pasaj even records the date of Yax Pasaj’s accession. As a king with a potentially questionable claim to the throne in a difficult political climate, this monument would have asserted his right to rule while providing a comprehensive reminder of the city’s glorious past.

Motifs:

- Cipactli / Crocodile

- Crossed bundles

- Feathered Shield

- Four

- Jaguar

- K'awiil

- Serpent Bar

- Tlaloc

- Turban

- Witz

See Also:

Sources:

- Baudez, Claude-François. 1994. Maya Sculpture of Copán: The Iconography. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Fash, Barbara W. 2004. “Early Classic Sculptural Development at Copan.” In Understanding Early Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, & Robert J. Sharer, 249-264. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

- Fash, William L, 1991. Scribes, Warriors, and Kings: The City of Copán and the Ancient Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Fash, William L., Barbara W. Fash, and Karla L. Davis-Salazar. 2004. "Setting the Stage: Origins of the Hieroglyphic Stairway on the Great Period Ending." In Understanding Early Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, & Robert J. Sharer, 65-84. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

- Herring, Adam. 2005. “A Borderland Colloquy: Altar Q, Copán, Honduras.” Art Bulletin, The 87(2): 194–229.

- Martin, Simon and Nikolai Grube. 2008. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames and Hudson

- Price, T. Douglas, James H. Burton, Robert J. Sharer, Jane E. Buikstra, Lori E. Wright, Loa P. Traxler, and Katherine A. Miller. 2010. "Kings and Commoners at Copan: Isotopic Evidence for Origins and Movement in the Classic Maya Period." Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 29 (1): 15-32.

- Sdouz, Gert. 2015. Altar Q Copan Honduras: A tour through the illustrations of one of the Maya’s most interesting monuments. Vienna: Wien.

- Stuart, David. 2004. "The Beginnings of the Copan Dynasty: A Review of the Hieroglyphic and Historical Evidence" In Understanding Early Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, & Robert J. Sharer, 215-248. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

- Taube, Karl. 2004. "Structure 10L-16 and Its Early Classic Antecedents: Fire and the Evocation and Resurrection of K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo'". In Understanding Early Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, & Robert J. Sharer, 265-296.